One of the questions we have been asked most often over the last 18 months is whether bullying has gotten better or worse since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Early on, there was a concern that cyberbullying incidents in particular would increase as youth were spending more time online. Additionally, many young children were perhaps given premature access to technology with inadequate support or supervision as schools hurriedly moved to virtual educational activities and parents simply needed to survive the extended time children had at home. On the other hand, we have long known that bullying online is often connected to bullying at school and therefore fewer students at schools might translate to fewer problems online.

Despite these speculations, however, I’ve mostly had to respond to the question about bullying during the pandemic by saying that we simply don’t know. Recently, though, initial research has emerged to provide some insight about the nature and extent of bullying behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. And we also collected data about bullying during the pandemic that we are now able to share.

COVID-19 Bullying Research

There have been at least three studies that have attempted to assess whether the pandemic had an impact on bullying among adolescents. First, Tracy Vaillancourt and her colleagues from the University of Ottawa and elsewhere examined bullying (general, physical, verbal, social, and cyber) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among a sample of about 6,500 Canadian students. They found that school bullying was much higher among students in grades 4 through 12 before the start of the pandemic. Specifically, nearly 60% of students said they had been bullied prior to the pandemic compared to about 40% during the pandemic. Cyberbullying, on the other hand, only decreased marginally (13.8% pre-COVID to 11.5% during COVID).

Second, researchers at Boston University analyzed Google internet searches for bullying and cyberbullying and found that searches for these terms on that site dropped 30-40% when schools went to remote learning in the spring of 2020. This reduced level of inquiry about these problems continued into the 2020-2021 school year, though began to increase once schools began to re-open their doors in the spring of 2021. Researchers speculated that decreases in online searches for bullying correlated to reductions in the behaviors.

Finally, an analysis of keywords related to cyberbullying (e.g., “cyberbullying,” “cyberbully,” “internet bullying”) on Twitter in the early months of the pandemic showed an uptick in the frequency of these terms immediately following school closings and stay-at-home orders. It is uncertain whether these terms were tweeted as a means of identification of actual incidents of bullying online, or for some other reason.

Taken as a whole, each of these studies sheds some light on the problem of bullying during the COVID-19 pandemic, though each has its own limitations. In particular, analyses of Google searches and Twitter keywords are especially tenuous in their insights about actual bullying incidents (especially because the studies returned conflicting results).

Our COVID-19 Bullying Research

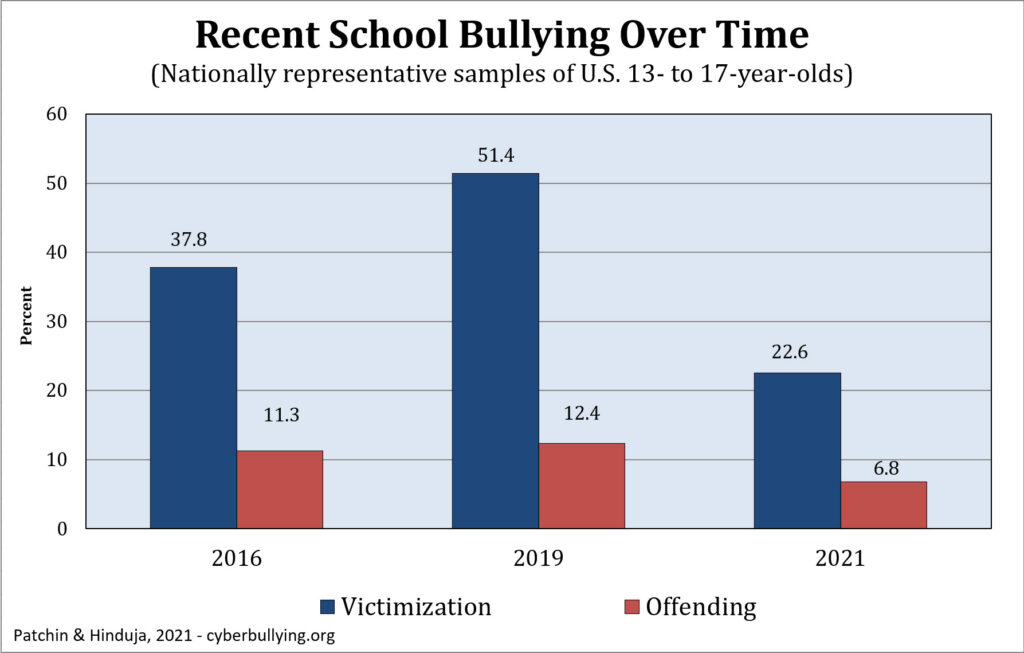

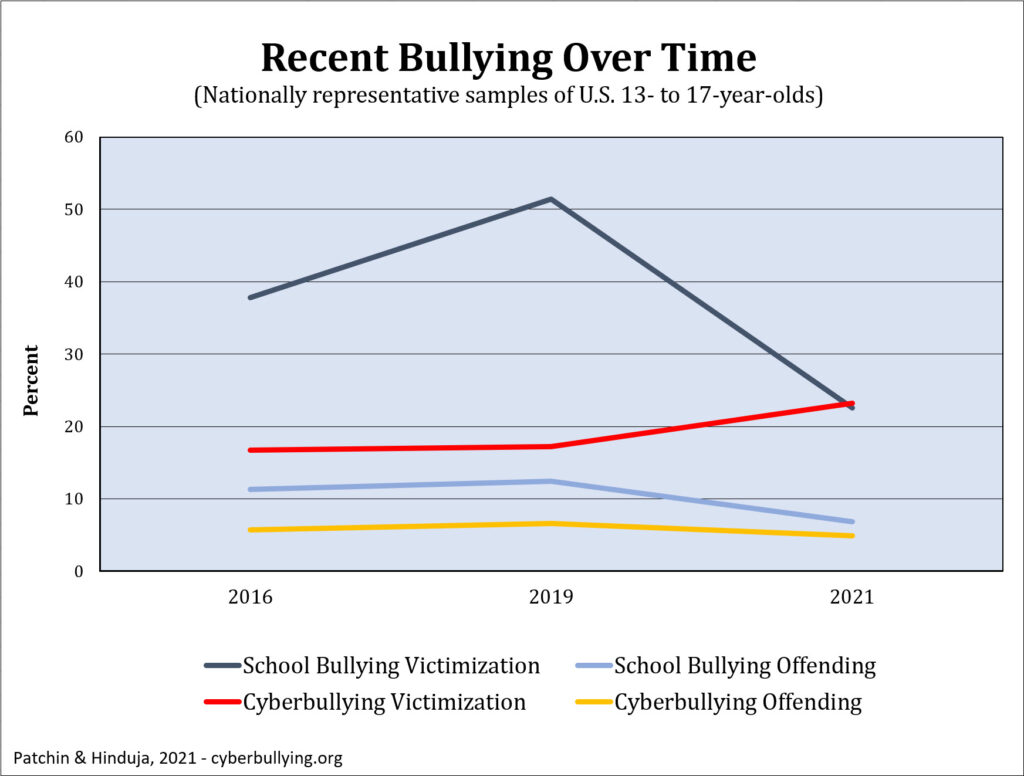

Sameer and I have been regularly collecting data on bullying and cyberbullying in the United States since 2004, most recently in the summer of 2021 (more on this latest project in a subsequent post). If we focus just on our last three studies, all of which are relatively large (2,500-4,700 participants) nationally-representative samples collected in 2016, 2019, and 2021 using the same methodology and identical instrument, we can evaluate some recent trends in bullying and cyberbullying behaviors over that time period. For example, in the spring of 2021, 22.6% of students said they had been bullied at school in the previous 30 days, compared to 51.4% in 2019 and 37.8% in 2016. A similarly steep drop was observed in self-reported school bullying offending behaviors in 2021. In 2016 and 2019, about 11-12% admitted that they had bullied others at school compared to 6.8% in 2021. In short, school bullying behaviors have undoubtedly dropped during the pandemic.

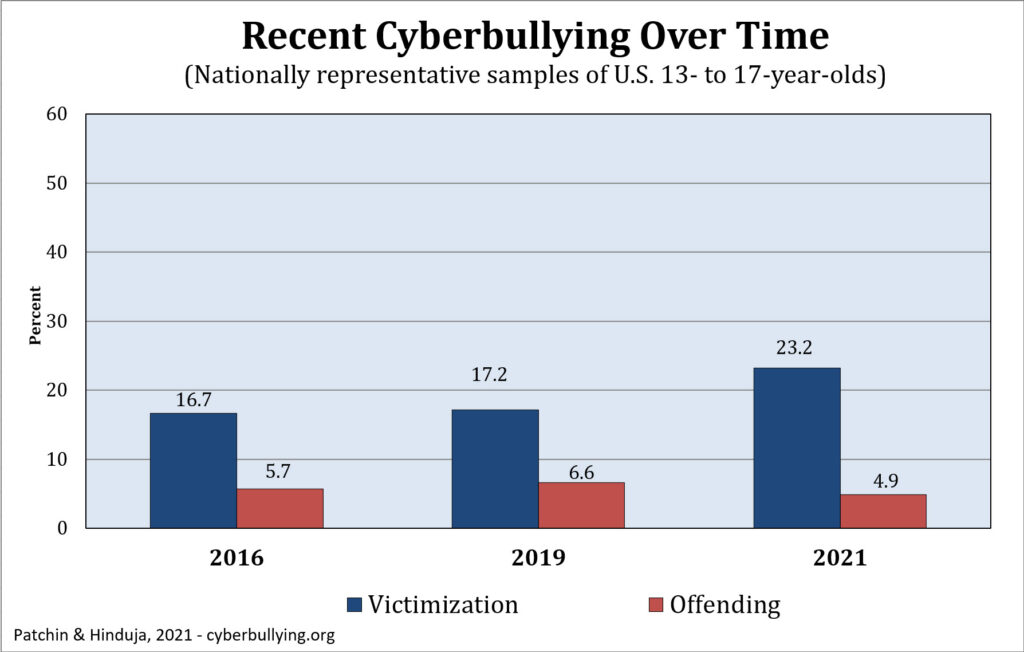

When it came to cyberbullying, however, the findings were less clear. More students reported that they had experienced recent cyberbullying in 2021 (22.6%) compared to previous years (17.2% in 2019 and 16.7% in 2016), but fewer students reported that they had cyberbullied others (4.9% in 2021 compared to 6.6% and 5.7% respectively in 2019 and 2016). It is also noteworthy that this is the first time in any of our studies that more students said they were bullied online than at school (though the difference was small [23.2% compared to 22.6%] and not statistically significant).

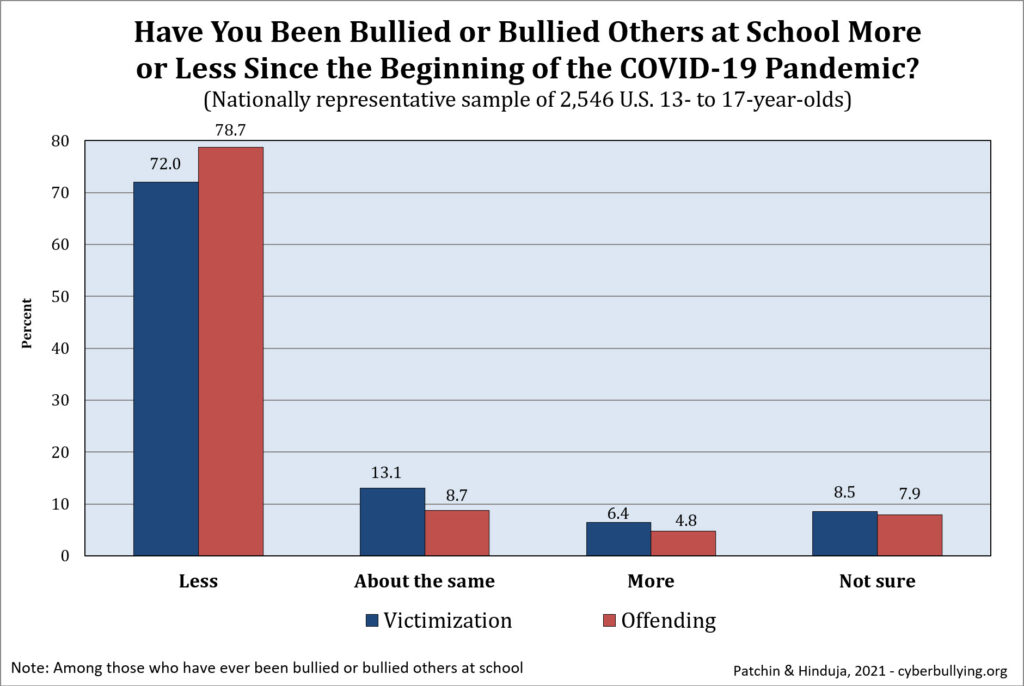

In addition to asking adolescents in our 2021 study to report if they had been bullied or cyberbullied in the last 30 days, we also asked whether they had been bullied (or had bullied others) at school or online more or less since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. When looking at responses to these questions we saw a similar pattern as observed above. That is, students overwhelmingly said that they had been bullied less at school since the start of the pandemic. Only about 6% of students said they had been bullied more at school during the pandemic.

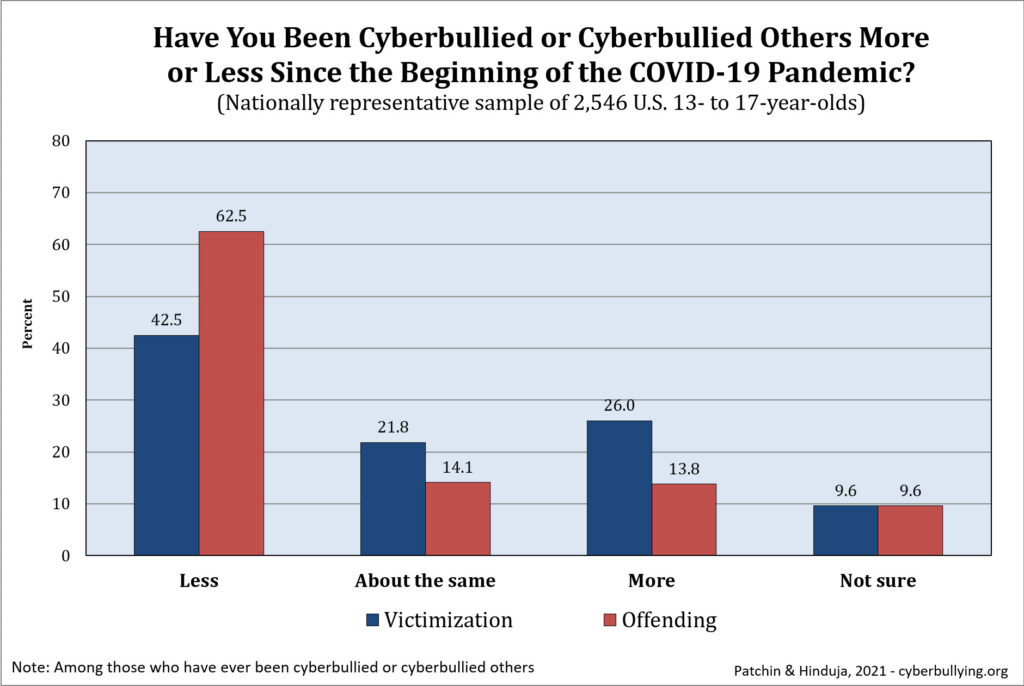

When it came to cyberbullying, most said they had been bullied online less or about the same as before, but about a quarter did report more cyberbullying during the pandemic. The same is generally true when we look at offending behaviors. The vast majority of students said they bullied or cyberbullied others less since the start of the pandemic.

Conclusion

So where does this leave us? Well, it is clear that the number of school bullying incidents dropped significantly during the pandemic. This is intuitive as fewer students were in schools generally and when they were many schools limited the number of students that could be in a particular classroom. Fewer students likely meant more supervision and fewer opportunities for misbehavior. When it came to cyberbullying, however, the results were less conclusive. I think it is safe to say that cyberbullying did not increase significantly over the last 18 months, but it likely didn’t decrease either. More youth are undoubtedly spending more time online, creating more opportunities for misbehavior.

It is clear that the number of school bullying incidents dropped significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

I do think it is promising that the cyberbullying numbers weren’t even higher. Despite dire predictions, online bullying didn’t seem to surge the way some had expected. It is possible that online conflict is occurring more often now than prior to the pandemic, but conflict isn’t always bullying. There are plenty of angry, frustrated, and frankly ignorant people (more adults than youth, in my experience) expressing their outrage on the internet these days. Social media comment wars are not necessarily bullying, but might be captured in some of the studies of keywords used in Google and on Twitter described above. Without context (such as knowing the relationship between the aggressor and target and whether the actions were intentionally hurtful and repeated over time) it is difficult to definitively determine if something posted online qualifies as bullying.

Another concern during the pandemic is whether students would have access to support if they were being bullied. Without physically being at school it could be more difficult for students to visit with a counselor, social worker, or psychologist to report, work through, and obtain help with any issues they might be confronting (including bullying). So even if overall bullying numbers are down, the consequences youth are facing because of these experiences could still be serious.

The other question on the minds of many is what is going to happen in the 2021-22 academic year? Most schools in my area are back to face-to-face instruction with few COVID-19 mitigation strategies (one local district is requiring masks, but none of the others are). Will we see an increase in school-based or online bullying with students back in schools? I’m personally concerned because my tween son’s school is not requiring face coverings, even though there will be no physical distancing and most of his classmates are currently ineligible for vaccination. Per parental instruction, he is wearing a mask. Will he be bullied if he is the only student in his class wearing a mask? Suffice it to say that there continue to be plenty of opportunities for kids to be mean to each other as the pandemic continues. And they will persist long after the current situation subsides.

Top image from Kelly Sikkema (unsplash)

The post Bullying During the COVID-19 Pandemic appeared first on Cyberbullying Research Center.