I pick my son up from school most days, and from his first day of kindergarten I got into the habit of routinely asking him two specific questions: 1) “How was your day?” and 2) “Was there any bullying?” I’d ask the latter question with a conspiratorial raise of my brow—as if asking him if they’d served Five Guys burgers for lunch in the cafeteria.

These daily interrogations started out as a lighthearted way to get my son to talk a little about his day, although I was also genuinely interested in the nature and extent of bullying at his school. He’d sat in the back row of enough of my presentations starting at an early age to know the basics of bullying and other trouble kids can get into at school and online. I didn’t expect much in terms of content for my research in the stories he would tell, but more than anything my goal was to open up a line of communication between him and I on this topic that most kids don’t like discussing. I hoped that these early low-stakes conversations about issues at school would make it easier for him to turn to me when more serious stuff came up. On top of that, research has shown that good parent-child communication can reduce the risk of experiencing bullying and cyberbullying as well as reduce the likelihood that a child participates in bullying.

In those early years he would report disagreements about classroom toys or incidents where one child didn’t want to play with another. I didn’t lecture him on the precise academic definitional attributes of bullying, but focused instead on how the behaviors made him or others feel. I also tried to instill some empathy, and encouraged him to intervene in ways that were appropriate (for example, playing with the classmate who might have felt left out or talking to his teacher).

As my son got older, the question about bullying at school came with eye-rolls or a drawn-out “nooooo!” with a tone of annoyance like I should already know that of course there wasn’t any bullying at school that day (or Five Guys burgers). I even started skipping the question, thinking it had fallen into the territory of bad dad-joke (as if there is such a thing). But the groundwork was laid, I hoped, for future conversations about difficult matters.

The Evolving Nature of Parent-Child Communication

At younger ages, children are generally forthcoming with their parents about issues, problems, and concerns. This changes over time, especially as kids move through middle school and into high school. As parents it is important that we capitalize on this pre-adolescent developmental time period where they will listen and talk to us. They need to know where we stand on important moral issues, of course, but they also need to know that they can come to us if they run into trouble. Hopefully we respond in a thoughtful and helpful way. (If you need help talking to your kids about bullying, see our Parent Resources.)

Psychoanalysts identify puberty as an important turning point in the nature of parent-child communication. At this stage of development parents typically give their children more privileges, autonomy, and privacy, creating fewer opportunities for one-to-one conversations. On top of that, hormonal and other biochemical fluctuations and increasing deidealization (kids begin to realize that their parents aren’t perfect!) can create significant conflict and avoidance. This varies a bit by gender, with boys and girls both becoming more private and secretive in early adolescence but boys continuing on this secretive trajectory throughout adolescence while girls typically return to open communication with parents during middle adolescence. Nevertheless, both boys and girls are more likely to confide in friends than parents during this time period.

Technology probably exacerbates and might even accelerate these patterns. As kids are given access to technology at younger and younger ages, they are able to communicate with friends and develop new connections from outside the familial unit. Instead of being stuck watching “Must See TV” with Mom and Dad, children today can play online video games and live chat via social media apps with their friends. It’s also more difficult to talk with children during long car rides now compared a generation ago as their devices allow for distractions and ready access to peers. This is not to suggest that we snatch the tech right out of their developing hands. The positives of technology unquestionably outweigh the negatives, especially in the era of COVID and with proper guidance. We simply need to be more intentional with our efforts to connect with our kids.

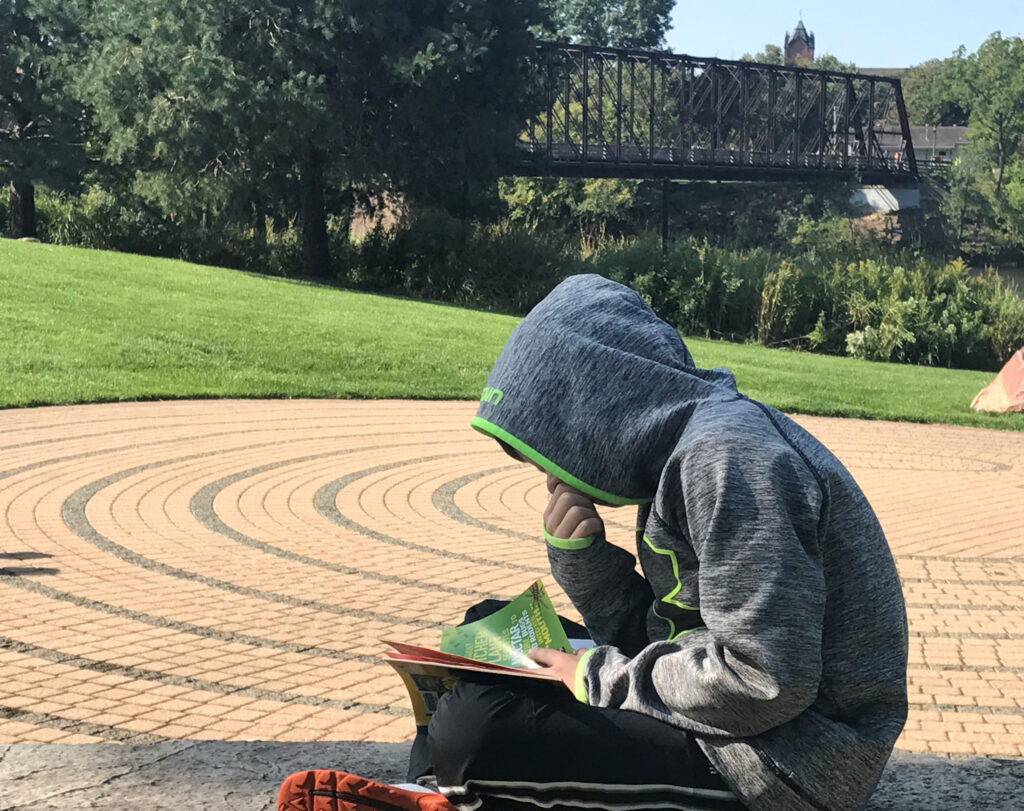

Since the start of the COVID pandemic, my son and I have spent a lot of one-on-one time together out on our local trails (me running, him riding his bike). This has been a wonderful chance to discuss a variety of topics, mostly mundane, but some more significant. I cherish these 45-90 minutes together 3-4 days each week. And surprisingly, he looked forward to them too. Because he is in his tween years, I know these opportunities are waning, and I want to take advantage of them as much as possible. I know that it will only get more difficult to connect with my kid over the next few years and now is the time to build a foundation of communication and trust that will hopefully get us through the next phase. As Brent Laursen and W. Andrew Collins observe in Parent-Child Communication in Adolescence: “Although relationship transformations inevitably impede family communication, greater parental investment in offspring, as indicated by a prior history of responsive parenting, is thought to provide a foundation of warmth and respect that may enable both parties to transcend the difficulties of adolescence.”

Practice Pays Off

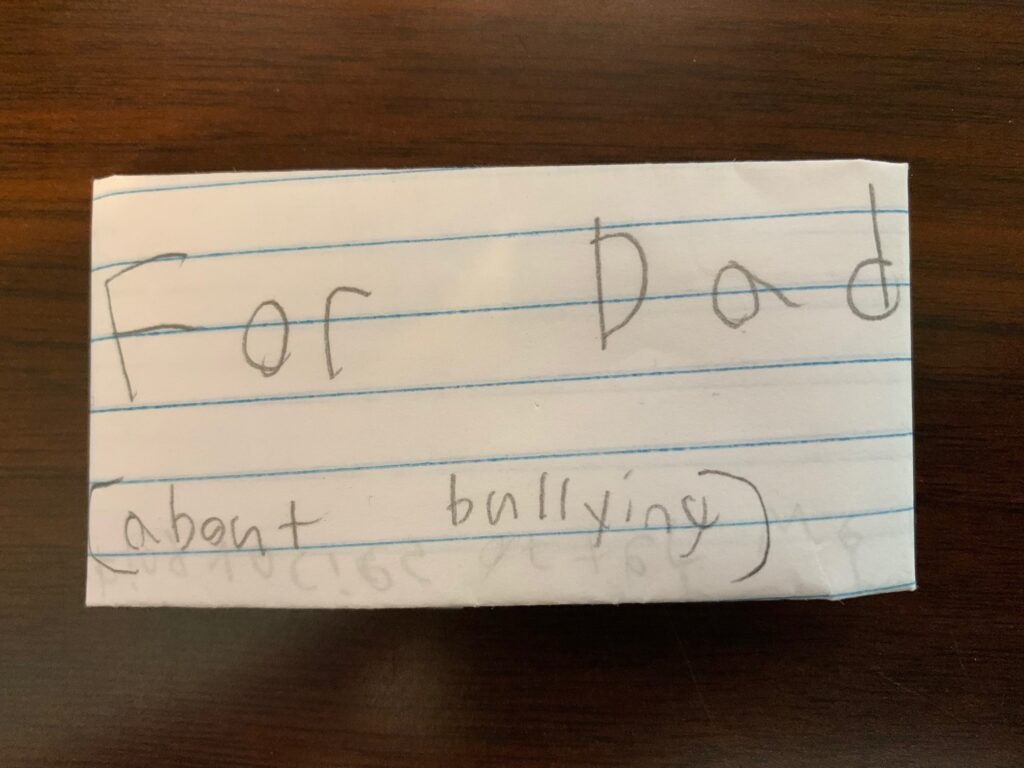

Then it happened. When I picked my son up from school not long ago, he handed me a painstakingly folded sheet of lined notebook paper with the carefully pencil-printed label: “For Dad (about bullying).”

The specific details of this particular incident are not all that important (he was not directly involved), but I was heartened by the fact that my son was open with me about it. Apparently the years of legwork to cultivate this relationship have paid off to the point that he willingly volunteered this information. He said he wrote it down so he wouldn’t forget to tell me about it. I thanked him for confiding in me and on the drive home from school that day we discussed what he did and how he felt in the moment, and what more he possibly could have done. He told me that he thought he and the teacher handled it ok and that the classmate who was targeted seemed better by the end of the day. I encouraged him to continue to let me know if there were problems at school, but also told him that I was happy that he knew what to do when it happened.

Now if I could only figure out how to improve the school lunch menu.

The post Inoculate Against Bullying by Chatting with your Children appeared first on Cyberbullying Research Center.